|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

After the starship orbital test, there were a lot of strong opinions flying around the subreddits, the twitters, and the facebooks.

I read a bunch of remarks and it was pretty clear that there were a lot of people out there who did not have - how can I say it nicely - a good grasp of the underlying issues.

Hence the title of this video.

However, I didn't think anybody would interested in watching a video about my shocking assertion that there are actually people on the internet who are ill-informed, so I've chosen to do something that I hope will be more constructive...

I'm going to talk about three questions...

Number 1: Why do people behave this way. How can they be so certain and so wrong?

Letter B: How can one self-identify being in this state?

Roman numeral III: What can one do to be better informed and move out of this state.

We'll start with the first question, which gives me the opportunity to talk one of my favorite studies in the field of psychology.

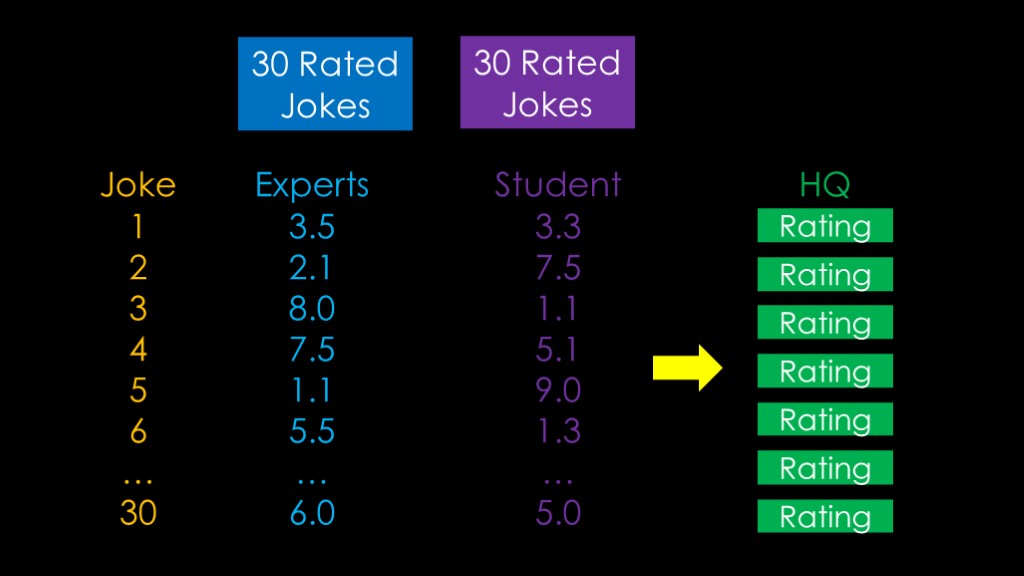

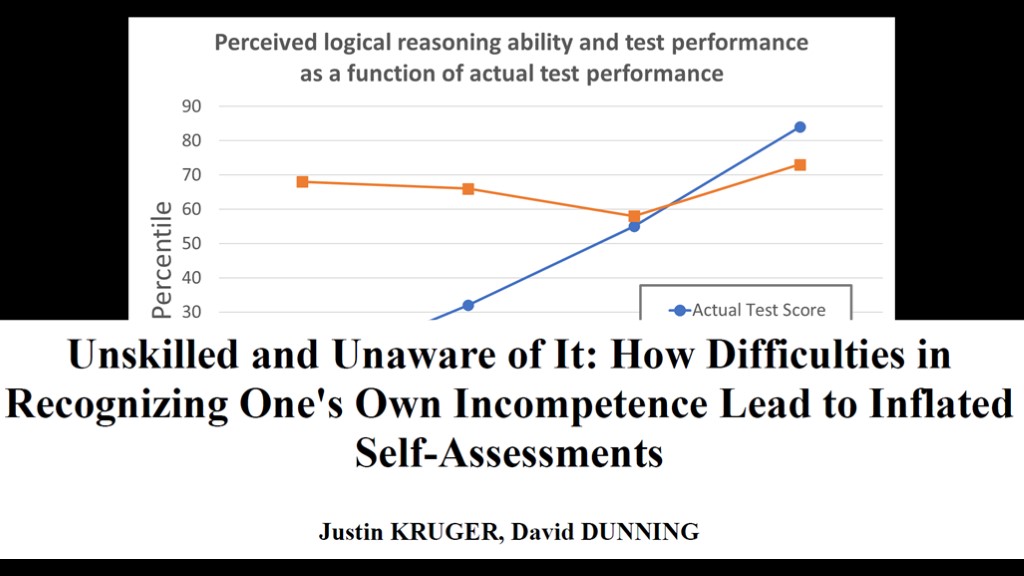

This study was published way back in 1999, and the topic of the study was humor.

Two researchers came up with 30 jokes that they believed exhibited varying degrees of humor. (Humority? There's strangely not a good word for this in English).

They were not experts in humor, so they then recruited 8 professional comedians who rated each joke on a scale of 1 to 11, with 1 meaning not at all funny and 11 meaning very funny.

The paper is silent on why they chose that range, but my guess is that it had something to do with Nigel Tufnel.

That gives them 30 jokes with expert ratings of how funny each of them is.

They then recruited 65 psychology undergrads from cornell university, and asked them to rate the jokes.

That gives us one expert set of ratings, plus a set of ratings for each student.

Those of you who know about research methods can predict the next step - they took the expert ratings and the students ratings for each joke and compared them, and produced a correlation number that indicated how closely each student joke rating correlated to the expert joke rating.

Those correlations are averaged, and that gives a rating on how well the student aligned with the experts - a sort of "humor quotient"

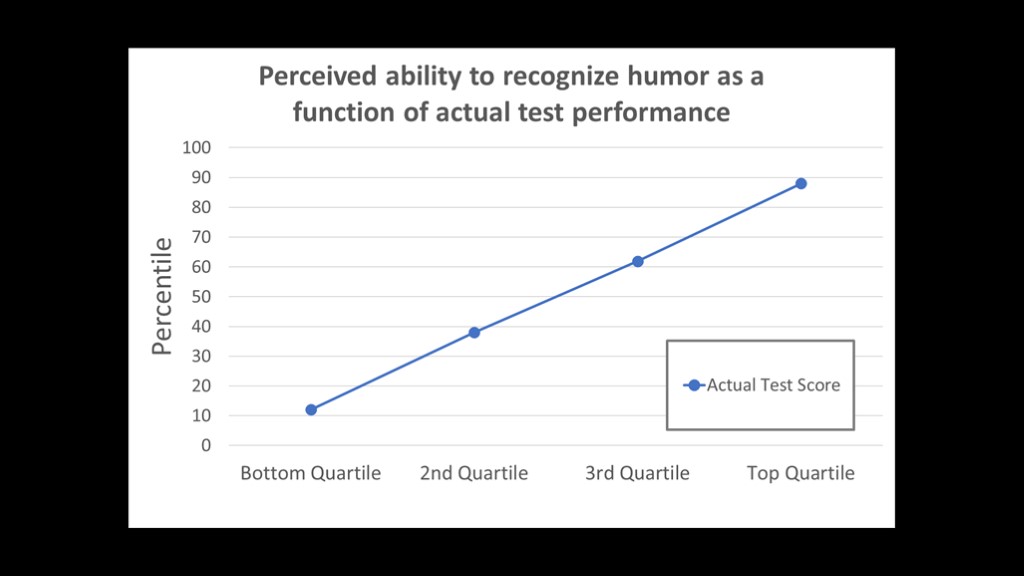

They then took the students and divided them into four groups, or quartiles, based upon those quotients. The 25% of the group that got the lowest scores went into the bottom quartile, the next highest scores in the second quartile, and so on for the third and top quartiles.

This is merely to group the students together into four groups based on humor quotient. We can then draw this graph.

It doesn't really tell us anything except that different people have different abilities, which is hardly a surprising outcome.

But there was something else they did, one other bit of data that they collected for each of the students.

They asked each student to please compare your ability to recognize what's funny with that of the average Cornell student.

They gave them a 0 to 100 scale, with "I'm at the very bottom" corresponding to zero, I'm exactly average corresponding to 50, and I'm at the very top corresponding to 100.

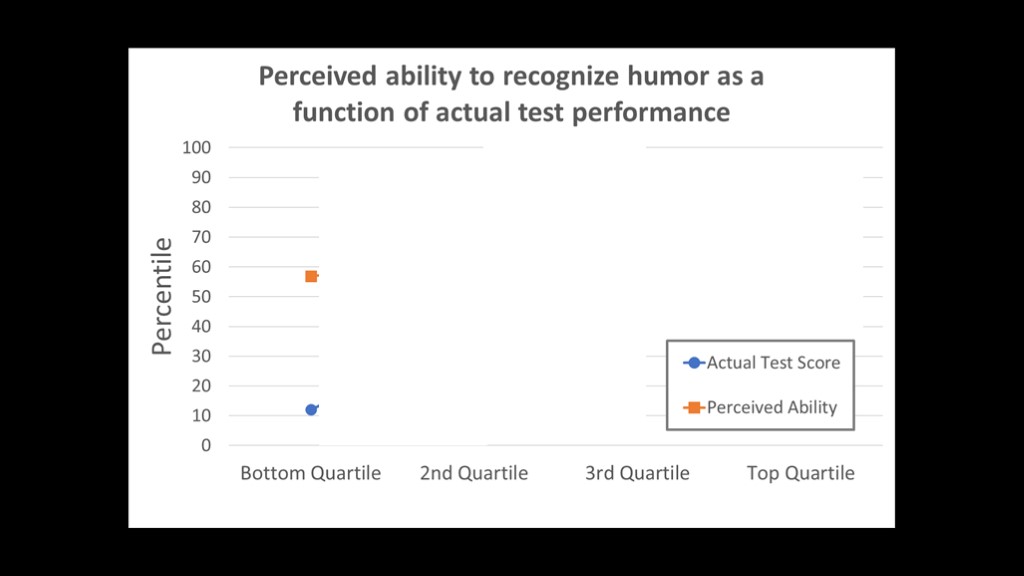

That number is their humor quotient perceived ability, and we're going to compare it to the rating they got when they rated the jokes.

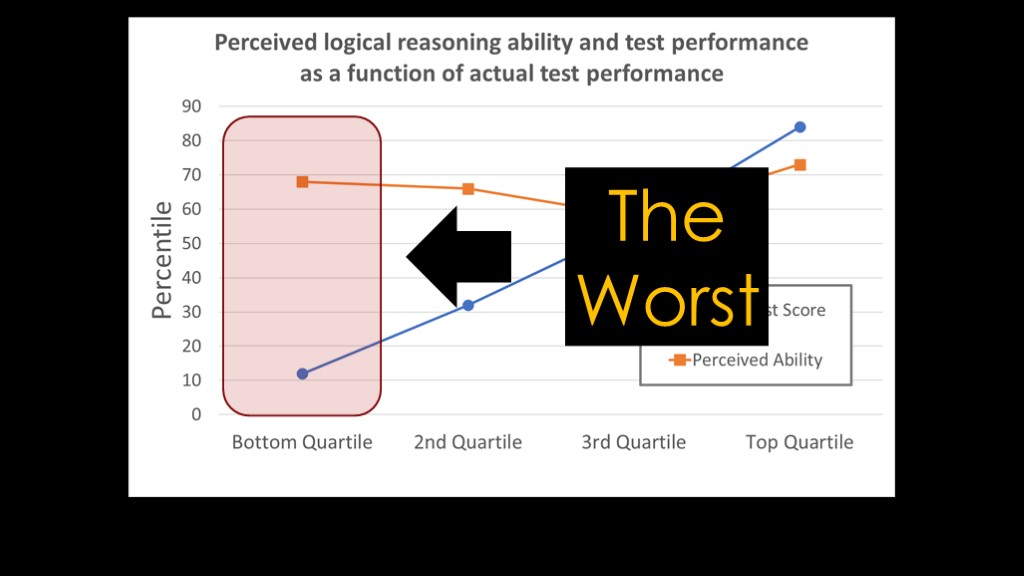

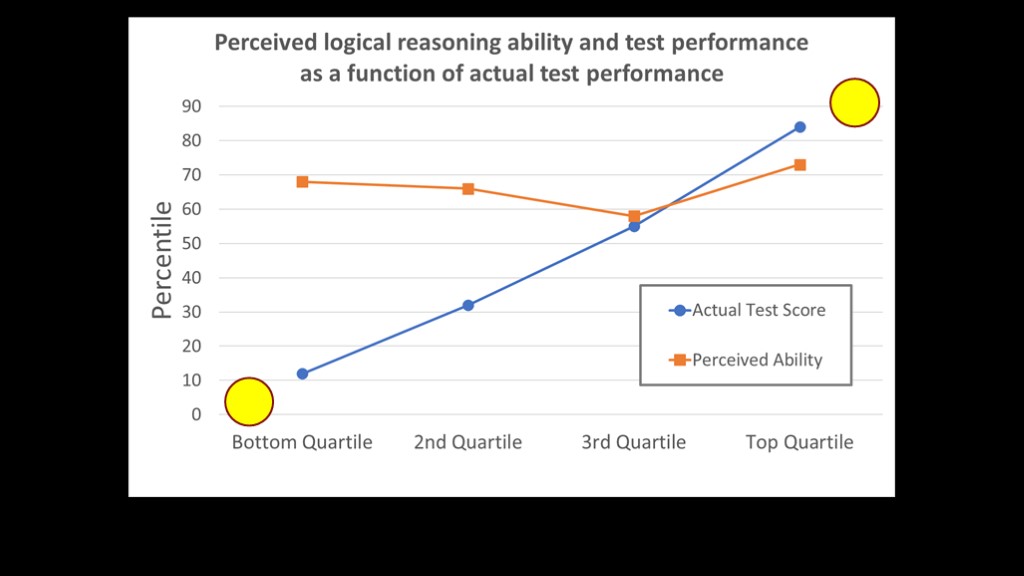

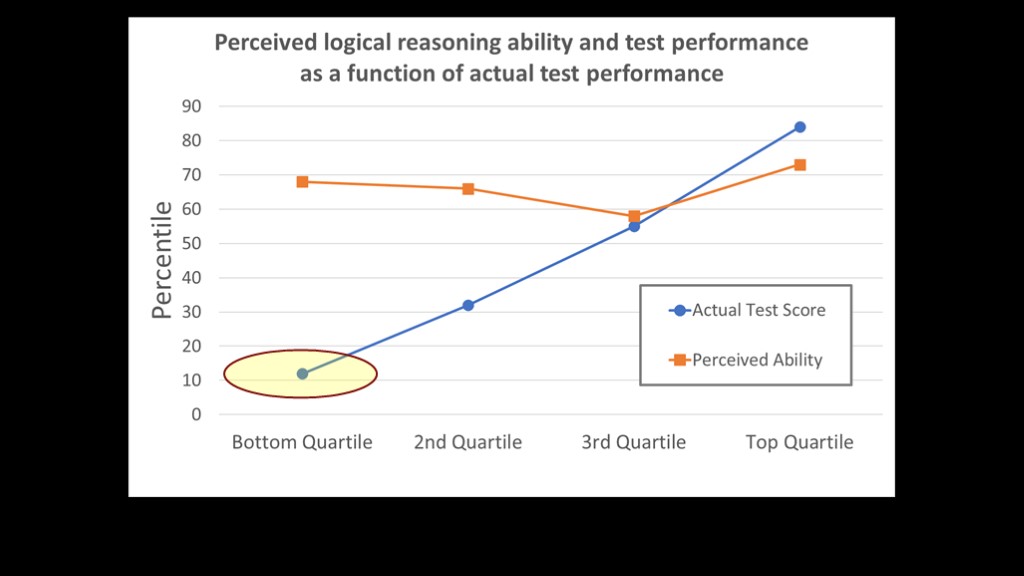

Here we see the actual performance of the bottom quartile in blue along with their average self-rating in orange.

The bottom quartile had an average performance at the 12th percentile, but they believed their ability was at the 58th percentile for an overestimate of 46 points. They were very poor at determining what was funny, but they thought they were better than average.

Moving up to the second quartile, this group had an average performance at the 37th percentile, and estimated they were at the 60th percentile, 23 points above their actual performance.

In the third quartile, the difference shrinks to 8 points. This group is pretty good at evaluating themselves.

In the top quartile, we see a reversal. Their actual test score is 87 and their perceived ability is only 75, so this group underestimates their actual ability by 12 points.

The paper says the following about these results.

(read)

But maybe, just maybe, humor isn't a good topic of study.

So they did another test looking at logical reasoning. It shows the same effect, but the bottom quartile here overestimates their ability by 56 points.

Some of you have probably figured out what study I'm talking about.

Here's the title of the paper.

(read)

You can see the authors were David *Dunning* and Justin *Kruger*, and this is the paper that popularized what is known as the "dunning kruger effect".

When I talk about this, I get a very common reaction to the bottom quartile.

It's something like, "I work with people like this and they are *the worst*."

Which amusingly, is people demonstrating that they are in the bottom quartile when it comes to their understanding of the Dunning Kruger effect. It's very meta.

The Dunning Kruger effect is about ability in a *specific area*. You might be world-class in one area, not only in the top 25% but in the top 5%. And you might be at the absolute bottom in another area.

Dunning Kruger is a general result - whenever you are working in an area where you are in the bottom quartile, you are not capable of evaluating your proficiency in that area.

It's just part of being human.

And therefore, what I'm saying is that those uninformed opinions that I was seeing are mostly coming from people who are in the bottom quartile of a specific topic.

Hundreds of people suddenly became experts on flame deflectors and concrete repair despite having no real experience or expertise in the area.

If you are in the top quartile of any area, you will notice the people in the bottom quartile. Just remember that you are assuredly in the bottom quartile in other areas.

Which takes us to the second question:

Can one identify being in this state?

It seems problematic - Dunning and Kruger wrote that being in the bottom quadrant means you can't identify that you are in the bottom quadrant.

But I think there are some symptoms that one can learn to recognize.

Number 1: These people are idiots.

If you find yourself with this opinion, you are almost assuredly in the bottom quadrant.

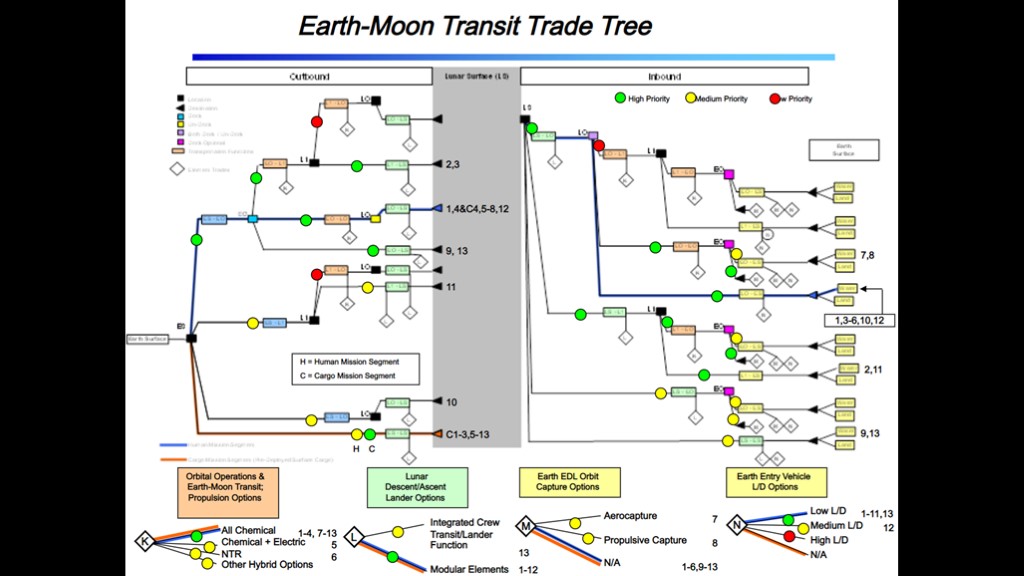

Pretty much any engineering organization will have done a trade study, also known as a "trade-off study" or simple "trades".

(read)

Here's on that I found that looks at different methods of getting from the earth to the moon.

Trades take the professionals a lot of time and effort to do well and the decisions aren't always clear cut.

If you don't understand the alternatives and you think the decision is easy, you are in the bottom quadrant.

If you are wanting to give your "hot take" on a situation, you are in the bottom quadrant.

A related sign is "they should just..."

I was going to call this "simplistic solutions", but "they should just" is so often used that I think it's a better label.

Here are some examples:

(read)

The "just" part is the indication of a simplistic statement about what is almost always a very complex issue. There are generally very obvious reasons that "they should just" solutions don't work.

There is the related "why don't the just?", which at least adds in some uncertainty but is generally the same attitude.

Number 3: Certainty...

Here's a question for you. Is liquid methane a better fuel than liquid hydrogen? There's a very straightforward answer to this question....

It depends...

It depends on a bunch of different things. What is the scenario, what are the goals, what constraints do you have, is cost more important than performance or vice versa, etc.

Experts are experts because they understand that the world is not simple, there are always tradeoffs and they are often complex. That is the whole point of doing trade studies.

If you are very certain about the answer to a question like this, you are likely in the bottom quadrant.

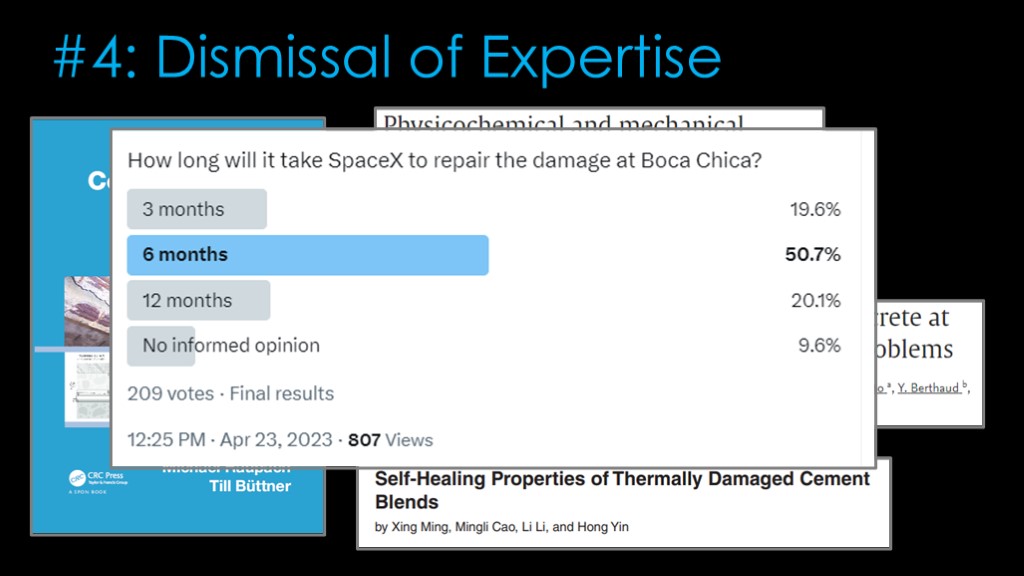

Number 4: Dismissal of Expertise

There are experts on pretty much every topic.

Not only are there books on concrete repair, there are numerous research papers on thermally damaged concrete. Some people literally spend their whole career on this topic.

That is not to say that experts are always right. Just that you need high-level understanding of a topic and the details of the expert analysis to determine if they are right.

I asked on twitter how long people thought it would take to repair the damage at Boca Chica, and these are the responses I got. About 90% of people expressed an opinion, but I'm not clear how anybody came up with a number.

And yes, surveys like this are fun and I respond to some of them myself, but they rarely generate useful predictions.

And our final question, what can one do to be better informed?

First, read the Wikipedia article on a topic. The space-related ones are generally quite good and the vast majority of their information is correct.

This is the entry level to being somewhat informed, and I'm surprised at the number of people who do not take this basic step.

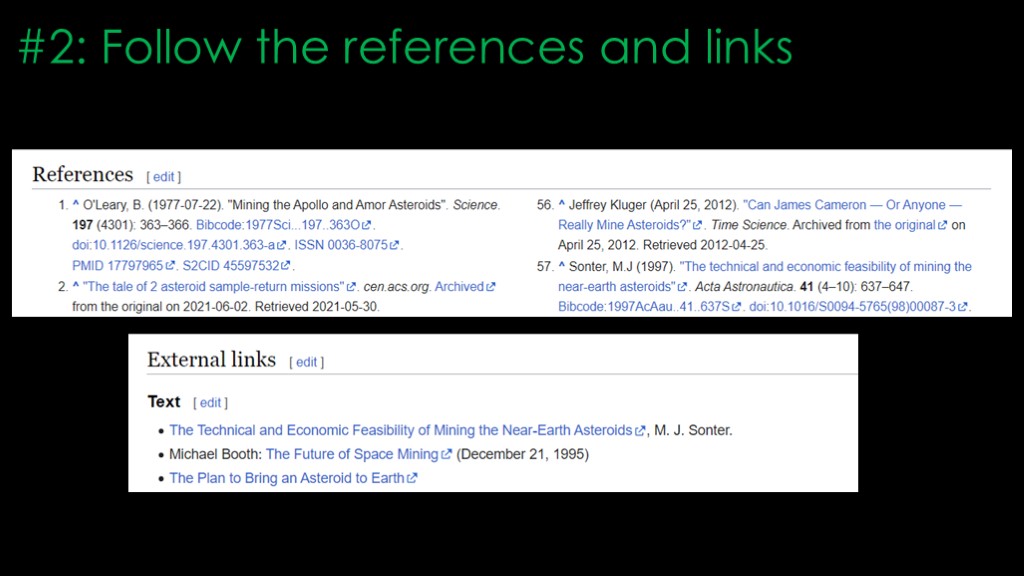

Follow the references and links.

If you really want to understand a topic, you're going to need to read original sources. You will usually find some links from the Wikipedia articles.

#3: Do deeper research

Google scholar is your friend. This will *mostly* point you to more reliable information, though I'll note that you will find a lot of articles and studies that are written by *advocates*, so they may be one-sided. But they are interesting because they are in more depth, though that also makes them much harder to read in general.

You will find that some articles are available in PDF, but many are behind a paywall.

Sci-hub is a site of dubious legality that allows you to access many papers that would normally be behind a paywall. Because of the legal issues, it tends to move around a lot so you'll need to search for it. Try using "where is sci hub" as your search, and if you don't see this page, you're probably on a site you don't want to be on.

If you have a university affiliation, you may be able to access articles that way, and your local library may also provide some access.

If you find a paper that's useful, I highly recommend downloading the pdf and saving it. Not only do papers sometimes go away, it's maddening when you know there's a paper out there but you are unable to summon a query that finds it.

For anything *technical* from NASA, the NASA technical reports server is a good place to start, though prepare to be a bit frustrated by the search functionality.

There's also the NASA image and video library which is either maddeningly incomplete or very poorly indexed; I am regularly frustrated by my inability to find NASA images that I know exist.

Note that the NASA centers maintain their own sites that may also have technical information.

If you are interested in speculative information, there is no better site that Winchell Chung's atomic rockets site.

#6 Don't watch videos...

Strange advice from somebody who has a youtube channel on space, but the percentage of bad space videos on youtube is pretty high.

My real advice is to be choosy - you know the things that help you identify when somebody is in the bottom quadrant of a specific topic, and keep those in mind.

I'm hoping that the information I've presented will help you understand what it's like to be in the bottom quadrant and how to get out of it, so that you suck less at space.

If you enjoyed this video, please write your hot take on it...